Mouldi FEHRI / Cinematunisien.com

Preamble :

Founded in April 1962, the Tunisian Federation of Amateur Filmmakers (FTCA), initially known until 1968 as the Association of Young Tunisian Filmmakers (AJCT), is now celebrating its 60th anniversary. This coincides with the 35TH International Amateur Film Festival of Kélibiawhich will be organised in this beautiful and welcoming town from 13 to 20 August 2022.

We take this (double) opportunity to salute all those (and there are many) who, throughout these years, have actively participated, through their production but also through their ideas and their struggles, in making this movement, still unique in the world, a fairly dynamic nucleus on the national cinematographic level and benefiting from a great reputation on the international level.

We are thinking at this time first of all of those who have left us. But we would also like to address those who, today, have the heavy (and no less exciting) task of preserving and even consolidating the achievements of this Federation, so that they may make the 35TH edition of FIFAK one of reflection, unity and renewal of this organisation.

- Birth of an unprecedented film movement

Dating back to the early 1960s, the birth of amateur cinema in Tunisia took place at a time when the seventh art was considered by most people as a simple means of entertainment imported from abroad. The very idea of a national production was practically unthinkable (at least for the time being) for both the public and the authorities.

Obviously, after independence, the first concerns of the Tunisian political power were essentially to set up the basic structures of the state, giving priority to public administration, health, national education and, in part, urban planning. Culture in general and cinema in particular were far from being a priority. The budget of the “Ministry of Cultural Affairs” at the time hardly exceeded 0.5% of the overall state budget. In these conditions, the cinema had practically no chance of being able to count on the financial support of public authorities. As for the private sector, it was in fact very poorly organised and far from finding any interest in investing in any cultural field.

A hundred or so cinemas, mainly located in the big cities and inherited from the colonial period, nevertheless offered the public the possibility of seeing quite a few foreign films (French, Italian, American, Soviet, Egyptian, etc.). Despite a certain reserve on the part of conservative families, attendance at these cinemas, considered at the outset as a simple place of leisure and entertainment, above all, allowed a large number of young high school students to acquire a general cinematographic culture and to benefit from a space for communication, sociability and openness to the world.

This interest in the cinema was soon reinforced by the action of the FTCC (created in 1950 and directed by the late Tahar CHERIAA) whose clubs, spread throughout the country, were to succeed in attracting a large part of this public of film lovers and especially the young educated generation.

It is in this general context that a movement of amateur filmmakers was born in Tunisia. This will be a unique case both in Africa and in the Arab world.

It should be noted that at that time, when Tunisia had not yet made its first feature film, this young structure gradually succeeded in attracting a good number of young people and indirectly and effectively played the role of a real training centre (which did not say its name) for several generations of filmmakers.

The federation has always trained and supervised nearly 200 members (depending on the period and since the mid-1960s) in 15 to 20 clubs throughout the country, and provided them with the necessary means to make their films.

Since its creation, the FTCA has produced an average of 20 films per year and keeps (subject to confirmation) in precarious conditions between 500 and 700 films (16mm, super 8 and video), some of which were signed by directors who are today among the most famous Tunisian filmmakers, such as: FéridBoughedir, Omar Khlifi, Ahmed Khéchine, RidhaBéhi, Selma Baccar,TaiebLouhichi, or AbdelhafidBouassida.

It should also be noted that from the 1970s onwards, this young organisationalso embarked on a close collaboration with similar associations (i.e. ACT and FTCC) in order to achieve together the construction of a national and democratic culture, thanks to the popularisation of cinematographic techniques and the audiovisual memorising of heritage, but also to provide regular support to the liberation movements, through the organisation of support events and the dissemination of film documents during the various festivals.

- 1960-1970: from AJCT to FTCA

- General historicalcontext :

In order to better understand and appreciate the starting conditions of this movement, it would be useful to place its birth in its general context, by briefly recalling the historical and political aspects of the time both in Tunisia and in the world.

We are, in fact, in the early 1960s, a period during which independence movements were multiplying and several formerly colonised countries were about to gain their independence. It was the gradual consecration of the principle of the ‘right of nations to self-determination’, the dislocation of the old colonial empires and the appearance of new countries on the concert of nations, becoming at the same time full members of the United Nations. However, their respective situations were still quite fragile, particularly in economic terms.

- Birth of the AJCT :

It is in these general conditions that in 1961, a young man of 22, passionate about images and cinema, the late Hassan BOUZRIBA, took the initiative to create the Association of Young Tunisian Filmmakers (later renamed FTCA). He became the 1er founding president.

In 1958, he had already bought an 8 mm camera which he used mainly to film his family members, their parties, holidays and other trips or ceremonies. At the same time, he followed closely and with great interest the work of Omar KHLIFI who had at the time an Association in Kheireddine (Northern suburb of Tunis) and who had just made an amateur film called “HALIMA”.

H.BOUZRIBA decided then, with some friends, to create his own Association which he called “AJCT”, with a 1er club or simple local in HALFAOUIN, in a small alley of Tunis. It was, in fact, an old small goods warehouse where there was just a table and some chairs.

The founding members were :

- Hassan BOUZRIBA: President

- Ezzeddine MADANI: Vice-Chairman

- Taoufik BEN ROMDHANE: Secretary General (later moved to France)

- Ridha EZNEIDI : Treasurer

- Mohamed Moncef EL MITOUI: Member

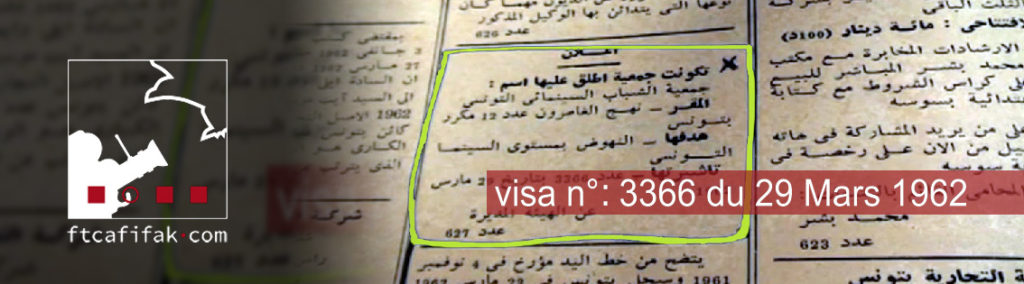

To launch the activity of this new association, it was necessary to wait for the “Visa” or “Authorisation of legal existence”, finally obtained in April 1962.

From there, they began to establish links with several partners who could provide them with assistance in terms of training and supervision (such as Mr. Salem SAYADI, a Tunisian director who graduated from IDHEC, or MrNoureddine BEN AMOR, also a graduate of IDHEC).

1ère important activity: a conference at the “Maison de culture Ibn Khaldoun” given by MrHamadi BEN MABROUK on the theme of “Editing, as the main axis of a film”. This was followed by other conferences on the same theme in Sousse, then in Sfax.

This led to the idea of setting up clubs in the different regions of the country.

In the meantime, the group of founders was enriched by the arrival of Ahmed HARZALLAH, who had just returned from Italy where he had studied and who had just joined the National Radio as a presenter. Ahmed HARZALLAH joined the group, not as an amateur, but as a trainer for the supervision of amateurs.

At the same time and by coincidence, the president of the FTCC (Tunisian Federation of Cinema Clubs), the late Tahar CHERIAA was appointed to the Ministry of Culture as “Head of the Cinema Division” where he was soon joined by the late Nouri ZANZOURI. These appointments were soon to prove very beneficial for the new AJCT association.

Then several other people joined the AJCT, like Abdelkader BEN ROMDHANE, Habib CHEBIL…

The real starting point: was to take place after a meeting that the founding members managed to have with President Habib BOURGUIBA on 06.09.1963 (in Le Kef): interested in the initiative of these young people, he decided to help them first of all financially, but also by asking the Municipality of Tunis to give them premises (that of No. 3, rue de Grèce in Tunis). It was this first aid that allowed them to acquire a 1ère Beaulieu 16 mm camera and film, to really start the production work.

In parallel and to develop the activity, clubs have been created in Sousse, Sfax and Kairouan.

The 1ère production was a series of documentaries including one on the “Bizerte Refinery”. Then, other films followed, including: “L’ennui” by Habib CHBIL and “Sabra” by Ahmed KHECHINE (Kairouan).

In the wake of this, the Hammam-Lif club (southern suburb of Tunis) was created and its activity was launched thanks to its first members, Moncef BEN MRAD, Ridha BACCAR, Salma Baccar, RaoufBEN MOUSLY: among these first films, “Réalités” by RaoufBEN MOSLY and “Réveil” by Salma BACCAR.

From then on, a confrontation of ideas took place between two schools: the one that defended “art for art’s sake” (Habib CHBIL) and the one that defended “committed cinema” (Moncef BEN MRAD).

It was in these conditions that the idea of the Festival was born, which was initially to take place in Hammamet in 1964. Finally it is Kélibia which was chosen and retained with the help of certain people like MrAbdelhak LASSOUED, a man known to be very open and who really wanted to encourage the AJCT.

In 1965, 2ème session of this festival, the Ministry gave 100 Tunisian Dinars as aid to the organisation. This was of course insignificant, but the festival took place despite all the difficulties.

Also in 1965, the AJCT organised its Congress in Gabesand took the opportunity to change its structure and name from an association to a Federation grouping all the clubs and called FTCA (FédérationTunisienne des Cinéastes Amateurs).

In 1966, the FTCA became a member of UNICA and thus the only Arab and African country (apart from South Africa) to be a member of this international organisation.

In January 1970, the UNICA Congress was held in Sousse, Tunisia. Ahmed BEN SALAH was then the Honorary President of the FTCA and the UNICA congressmen were received by BOURGUIBA.

This being the case, it should be noted that several well-known Tunisian artists first passed through the FTCA, such as Taoufik JEBALI, Samir AYADI, Mohamed DRISS and others. It was a bit like “their school”. They participated in training sessions at the “Centre d’InitiationCinématographique” without being members. The door of this centre created by the FTCA was, in fact, open to all those who wanted to be trained.

In 1968, the FTCA encountered its first internal difficulties, as it was to experience a general protest movement, concerning management, training and production methods. This would later lead to the famous ‘Reform’ text.

It was in fact Abdelwaheb BOUDEN, an amateur filmmaker from the Kairouan club, who was at the origin of this movement, after long contradictory discussions with other amateur filmmakers, such as Moncef BEN MRAD from the Hammam-Lif club. But he was very quickly joined by a large number of clubs who decided to support his own theses and to help him achieve the objectives of this reform, starting with the change of the national management and the establishment in its place of a “collegiate management” with new basic principles, more rational for training and production.

The same thing will then be progressively generalised and applied at the level of all the clubs of the federation.

- 1970-1980: Implementation of ‘The Reform

- General context

- In historical terms: in the early 1970s, the whole planet was experiencing the effects of the May 1968 protest movement in France. The notion of ‘authority’, in all its forms, was being challenged and more and more young people, especially in the developed countries, were expressing their opposition to consumer society, denouncing American imperialism (especially with its presence in Vietnam) and showing their support for the various revolutionary and/or liberation movements around the world.

In Tunisia, and without being directly linked to these protest phenomena in Western countries, youth organisationsmobilised to demand more rights, freedoms, justice and democracy. The student movement was illustrated at this level by the famous congress of the General Union of Tunisian Students (UGET) held in Korba in 1971. While the cultural movement, which was beginning to experience some reflection in its various sectors, was gradually embarking on a long process of restructuring, emancipation and clarification of its future objectives.

- At the national cultural level: at the time, it was the Tunisian Federation of Film Clubs (FTCC), which was then swept along by a wind of protest against the “established order” and in particular against the elitist form that dominated the entire film club circuit. In 1970, the national leadership was entrusted to a new generation of Tunisian high school students and young teachers. Determined to change everything, the first objective of this young national leadership was to put an end to the hegemony of French development workers over all the local structures of the Federation, and in particular to the monopoly they had over the choice of films and the organisation of debates. It should be said, by the way, that this situation had persisted since the colonial era and that it was therefore quite normal to turn the page.

By taking their Federation into their own hands, young Tunisian filmgoers have transformed both the form and content of the debates, which until then had been mere formal discussions between a few adult and intellectual initiates. Instead of these elitist and sometimes intimidating debates for the public, real free exchange sessions were set up, using simple language accessible to all participants. Thus (and especially from 1972 onwards), film clubs were no longer the privilege of an elite, nor the place for intellectual discussions that were sometimes of no obvious interest to the public. They were now open to young people and to all social strata, and at the same time allowed them to discuss the real and concrete problems evoked by certain films, trying to bring them closer to those of their own daily lives.

Very quickly, this new ‘realistic and national identity’ current managed to win the sympathy and support of the public and its members and, not surprisingly, ended up definitively replacing the ‘formalist and nostalgic’ current of the colonial period.

- The FTCA validates its great “Reform”.

It was in these conditions that the amateur filmmakers were to embark, between 1971 and 1973, on a gradual and radical transformation of the structures and objectives of their Federation. The changes envisaged and undertaken left nothing to chance and concerned the organisation of the Federation (the FTCA), its mode of operation and management, as well as its cultural objectives and its training and production practice. This global process, which had been long thought out, matured and prepared (since the end of 1968-69) essentially by one of the amateur filmmakers from the Kairouan club, Abdelwaheb BOUDEN, took the name of “The Great Reform of Amateur Cinema” and from the outset counted on the broad support of the various clubs at the time. From a Federation dominated and directed in all opacity by a few local notables, whose only production was the recording of their personal and family memories, or reports on the movements of political leaders, or even on some occasional neighbourhood festivities, the FTCA was going to metamorphose and experience a real radical transformation. This great “Reform” of Tunisian amateur cinema, which became the fundamental text of the whole structure, will put forward three fundamental principles, namely

- For collegial leadership: this first principle aims to empower amateur filmmakers, to end the privileges of their former self-appointed leaders and to establish a spirit of collegiality and democracy in all decision-making. It is true, however, that applied in a country ruled with a firm hand by a single party, tolerating no contestation, this principle was not only ahead of its time, but was likely to be rejected by the authorities and considered utopian by many.

- For a progressive training-production: the second principle insists on the need to rationalise training and production through the establishment of a progression by successive stages, both at the training and production levels. At the same time, a compulsory passage through photographic training was to allow all new members to be initiated into this technique before being able to access film training and production. The aim of all this was to prepare the future amateur filmmaker for a real mastery of writing through images and more particularly for a correct, readable and appreciable cinematographic expression.

- For a quality cinema open to society: the third principle is conditioned by a good application of the second. In fact, it allows the filmmaker who has mastered the successive stages of training to be able to present the public with a sufficiently correct (and therefore quality) production, and thus facilitate the reading and understanding of the message transmitted. This requirement of quality should in no way be interpreted as a defense of what might be called “art for art’s sake”. On the contrary, its only objective is to serve the theme and its clarity, especially since the principle emphasises the need to produce “a cinema open to society”. In other words, “La Réforme” encourages amateur filmmakers to produce works that are rooted in the reality of the country, dealing with subjects of people’s daily lives, but in a language that is polished and easily accessible to the audience.

- It is also distinguished by certain specificities

The FTCA’s raison d’être is obviously to produce films. But at the same time, it is to demystify the cinematographic tool and to allow as many people as possible to familiarise themselves with this technique, long considered inaccessible, mysterious and something that only an elite of professionals could master.

In an Arab-Muslim society such as Tunisia, where the oral tradition has no competition and where the word remains the most common means of expression, it is not always possible to succeed in such a task. And this is all the more difficult as expression through images requires financial resources that can be a heavy burden for a country whose wealth is rather limited, and even more so for a simple individual.

For all these reasons, the work accomplished by the FTCA, to this end and under generally difficult conditions, is far from negligible. In our opinion, it is certainly perfectible and often controversial, but it still deserves to be encouraged. Among its main specificities we can recall the fact that:

- It is a movement open to all Tunisians and especially to the youngest among them.

- Its clubs are located in different parts of the country.

- Its production is quantitatively very important: nearly 20 films per year (on average).

- Despite some technical and thematic shortcomings, the films he produces are certainly not lacking in interest.

- The subjects dealt with in his films (especially since 1971 and the introduction of the “Reform”) are generally rooted in national reality and try (as best they can) to reflect the concerns of the population in its diversity.

- The lack of sufficient financial means (at least until 1980) prevents him from making copies of all his films and from having the necessary conditions for the conservation and archiving of the negatives.

- And rooting its production in the Tunisian reality

The intention of the movement and its reform was indeed to bring amateur cinema closer to Tunisian society and to give it a cultural, social and political mission at the service of the Tunisian people. In order to achieve this, it also set itself, as its other main mission, to combat commercial cinema (which dominated the national market), to be its antithesis and to make the public aware of its socio-cultural identity.

Without opposing the fact that cinema could also be a means of entertainment and leisure, this new trend envisaged by “The Reformation” rejected, however, any use of film production as a means of escape from hardship or of diverting the public’s attention from its daily reality.

In accordance with this new conception of the function and role of amateur cinema, the FTCA decided to contribute to the production of a national, progressive and independent cinema, which above all reflects the national realities of Tunisia. This explains its close and permanent collaboration with the Association of Tunisian Filmmakers (professionals) and the Tunisian Federation of Film Clubs (FTCC).

Together and for many years, these three organisations had multiplied their joint actions to denounce the monopolisation of the national market by a most alienating commercial cinema, and to encourage the emergence and development of a true national cinema, without falling into any form of nationalism or a categorical rejection of all Western cinema.

It is in this context and on this subject that ABdelwahebBouden wrote that: “Nationalising should not only mean ending the administrative and economic domination of the large foreign film companies, but also and above all ending their economic system of production and their cultural model of cinema. […] Nationalising must mean producing a national cinema and not reproducing Western cinema in a national structure.

- FIFAK becomes the FTCA’s real showcase

Tunisian cinematography, which has always experienced enormous difficulties, particularly at the beginning, can nevertheless be proud of some unique achievements in the Arab-African world.

In this sense, and in addition to the JCC, the FIFAK created in 1964 by the FTCA and organised by it until 1973, constitutes without any doubt a rather remarkable achievement for all the national democratic forces and more particularly for the organisations and individuals who have made the cinema their favourite weapon in the struggle for the advent of a national and progressive culture in Tunisia.

However, the FIFAK, like any other important achievement, could not remain for long sheltered from the manoeuvres of the public authorities, which simply tended to stifle it. Everything was done, especially in the mid-1970s, to ensure that this international cultural event was taken over by the party in power in Tunisia at the time. And this could not be surprising, given the decisions of the congress of this party (the PSD) held in Monastir in 1975, which clearly showed the firm determination of its leaders to monopolise all sectors of public life. Indeed, nothing could be done outside the PSD structures, without its consent and especially against its own policy

From then on, the FIFAK gradually became a very special cultural event, arousing a lot of interest and covetousness, and at the same time it became a kind of ‘thermometer’ allowing (at each session) to measure the state of health of the FTCA, both internally and externally.

- 1973: an exemplary session

It was in 1973 that the FTCA organised the best session of this festival. And this success did not come about by chance. On the contrary, it was the result of two years of intense activity that the Federation experienced from 1971 onwards, when “The Reform” was adopted and implemented. This text, which restructured the amateur film movement in a radical way compared to what it had been and set out fundamental principles for the first time, was therefore no stranger to the smooth running of the 1973 Festival.

Thus, at the organisational level, a democratic method of operation decided upon and put into practice on the spot enabled the participants to elect, from among themselves, a set of committees, each responsible for a specific mission, and whose decisions were taken collectively. Similarly, the results in terms of production were encouraging, positive and remarkable.

- 1975: the greatturning point

All the amateur film-makers present at the 1975 Kelibia Festival, as well as the vast majority of journalists who covered it, were unanimous in considering this session to be a total failure: a failure both in terms of organisation and the cultural and artistic interest of the participating films. But it was also a failure in the sense that it was a clear step backwards from the democratic and progressive aspects of the Festival in its previous session.

As for the reasons for this failure, there were essentially two:

- The offensive of the Ministry of Cultural Affairs: in fact, following the directives of the Destourian Socialist Party, the said Ministry took over the effective management of the Festival. It invited foreign countries of its choice and selected the films on the basis of absolutely arbitrary criteria. Moreover, the Federation’s representatives on the Board of Directors, who were only deputies, could not carry any real weight and their opinions were probably the last to be taken into consideration. The real masters of the Festival were in fact administrators from the Ministry who had no connection with the film industry. This is the negative element that was the most decisive. But there is a second element that should not be ignored.

- The internal evolution of the Federation between 1973 and 1975 :

- A regressing training-production: in fact, just after the 1973 session, a good number of amateur filmmakers, who had acquired a valid training and who were at the origin of the change that gave rise to the text of “La Réforme”, having completed their secondary studies, left their native towns to begin higher studies at the University of Tunis or abroad. This gradually created a vacuum that was very difficult to fill (and quickly) in the various clubs of the Federation. It should be noted that this element was of great importance, since the majority of amateur filmmakers at the time were high school students.

The main point in all this is that the national film production presented at the 1975 Festival was the work of new members whose training was still in its infancy and certainly too inadequate. As a result, the technical and thematic level of all Tunisian films was simply mediocre.

- A basic understanding and misapplication of ‘The Reform’: here, too, a new situation was created by the departure of the old amateur filmmakers and the arrival of a large number of new members. This was not negative in itself, on the contrary. However, the problem was that the latter were from the outset rather poorly supervised and the explanation given to them of the text of “La Réforme”, of its general spirit and fundamental principles, was too inadequate and without any obvious clarity. The inevitable result of such a situation could only be a misapplication of this fundamental text, illustrated by improvisations at all levels and interpretations of the principles of “The Reformation” going in all directions. This has created an increasingly perilous situation for the future of the Federation.

- 1979: many mistakes, but still a success.

Once the 1975 session was over and its failure noted, the greatest debate among amateur filmmakers was to find the appropriate means of struggle that would lead to the Federation taking over the organisation of the Festival to make it once again the place and occasion for the promotion of a national and progressive culture.

Obviously, such a debate, occurring in the internal conditions of the Federation, to which we had already alluded, could not fail to give rise to difficulties and divergences between the members, which could be decisive, or even really dangerous for the future of this film movement itself.

In short, the Tunisian Federation of Amateur Filmmakers could not (or did not know how to) stay away from the various upheavals that the country as a whole was experiencing for three main reasons:

- It is a national organisation of pupils, students and civil servants. Therefore, the problems of the university as well as those of the new economic and political options of the country were automatically transferred to it.

- The public authorities, wishing to generalise and impose their new orientations, did not hesitate, particularly following the famous PSD congress in Monastir (1975), to launch a real offensive in the cultural field.

Thus, the FTCA, which was still preoccupied with the problems of applying ‘The Reform’, found itself obliged to confront a new situation, namely the rapid, unexpected and more or less anarchic politicisation of its cultural debate. This was totally incompatible with its internal reality and the objectives for which it was created. It is also true that, like most Tunisians, the vast majority of amateur filmmakers were not very (or not at all) politicised. This meant that the debate (in its new form) was completely distorted from the start.

- In addition to all these elements, the FTCA had to wait four years for the Ministry of Cultural Affairs to finally give in to the resistance of the amateur filmmakers. The 9ème session of the Festival, which should have been held in 1977, could not take place until two years later. It was, in fact, from 7 to 14 July 1979, that the town of Kélibia hosted the International Amateur Film Festival again.

This is how the 9ème session of the International Amateur Film Festival of Kelibia (1979) was prepared. And it is on this basis that the following facts can be explained:

- Most of the Tunisian films presented at the 9ème session were so technically mediocre that one could not help but feel pessimistic about the future of this movement, which, without realising it, was moving further and further away from the very essence of its existence, namely, methodical film training, with a view to a production that was at least acceptable and technically readable. Indeed, even if a film carries an important message (even one that is committed to a given cause), it can easily lose its value and interest in the eyes of the public if its cinematographic writing is very little or not at all careful. This was unfortunately the case with the Tunisian films in this session.

That is why, at this level and during this difficult period, the Federation needed a new lease of life, in order to be really able to play an important role in the emergence of a national, independent and progressive cinema.

- The organisation of the Festival (between 7 and 14 July 1979) was far from democratic. The rather positive example of 1973 could not be repeated, despite the insistence of several participants. On the contrary, the members of the federal bureau and FTCA representatives on the Festival’s steering committee monopolised all the responsibilities, with the help of members arbitrarily chosen before the Festival. This created a kind of frustration among the rest of the participants and led them to behave in a marginal way.

- Despite the adoption of new regulations, which gave the FTCA a greater role than it had had in 1975, it was noted that the Ministry of Cultural Affairs had found no difficulty in imposing certain repressive measures likely to disrupt the smooth running of this event. This had the immediate effect of dividing amateur filmmakers on the manner and tactics to follow to prevent the application of this measure, which could later constitute a very serious precedent. In fact, this led to 10 clubs withdrawing their films (a dozen) from the competition.

We can therefore see that the government was able to keep a certain margin of manoeuvre for itself, which allowed it to intervene in a fairly decisive but very subtle way.

- Taking advantage of all the mistakes made during the Festival (1979), the Ministry of Cultural Affairs did not hesitate to create an incident during the closing ceremony, hoping to find an excuse to crush this event deemed too independent. Indeed, the reading of the international jury’s report was interrupted by the minister, who declared that the report was “a political manifesto unrelated to the event in question”. The members of the jury insisted on the need to complete the reading of their report before the proclamation of the prize list. In the face of the insistence of some and the refusal of others, an atmosphere of radical disagreement took hold of the closing session, which had to be interrupted without the results being announced and the prizes distributed.